hurling

The History

Hurling is an outdoor team game of ancient Gaelic and Irish origin, administered by the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA). The game has prehistoric origins, and has been played for 3,000 years. One of Ireland’s native Gaelic games, it shares a number of features with Gaelic football, such as the field and goals, the number of players, and much terminology. There is a similar game for women called camogie. It shares a common Gaelic root with the sport of shinty, which is played predominantly in Scotland.

The game is now played all over the world, and is growing in popularity every year. The North American Championships were held in Seattle in 2016, with the Seattle Gaels hurling team winning a national championship.

The Objective

The objective of the game is for players to use a wooden stick called a hurley (in Irish a camán) to hit a small ball called a sliotar between the opponent’s goalposts either over the crossbar for one point, or under the crossbar into a net guarded by a goalkeeper for one goal, which is equivalent to three points. The sliotar can be caught in the hand and carried for not more than four steps, struck in the air, or struck on the ground with the hurley. It can be kicked, or slapped with an open hand (the hand pass) for short-range passing. A player who wants to carry the ball for more than four steps has to bounce or balance the sliotar on the end of the stick, and the ball can only be handled twice while in his possession.

Players per Side

Length of Pitch

Width of Pitch

Playing field

A hurling pitch is similar in some respects to a rugby pitch but larger. The grass pitch is rectangular, stretching 130–145 metres (140–160 yards) long and 80–90 m (90–100 yd) wide. There are H-shaped goalposts at each end, formed by two posts, which are usually 6–7 metres (20–23 feet) high, set 6.5 m (21 ft) apart, and connected 2.5 m (8.2 ft) above the ground by a crossbar. A net extending behind the goal is attached to the crossbar and lower goal posts. The same pitch is used for Gaelic football; the GAA, which organizes both sports, decided this to facilitate dual usage. Lines are marked at distances of 14 yards, 21 yards and 65 yards (45 yards for Gaelic Football) from each end-line. Shorter pitches and smaller goals are used by youth teams.

Teams

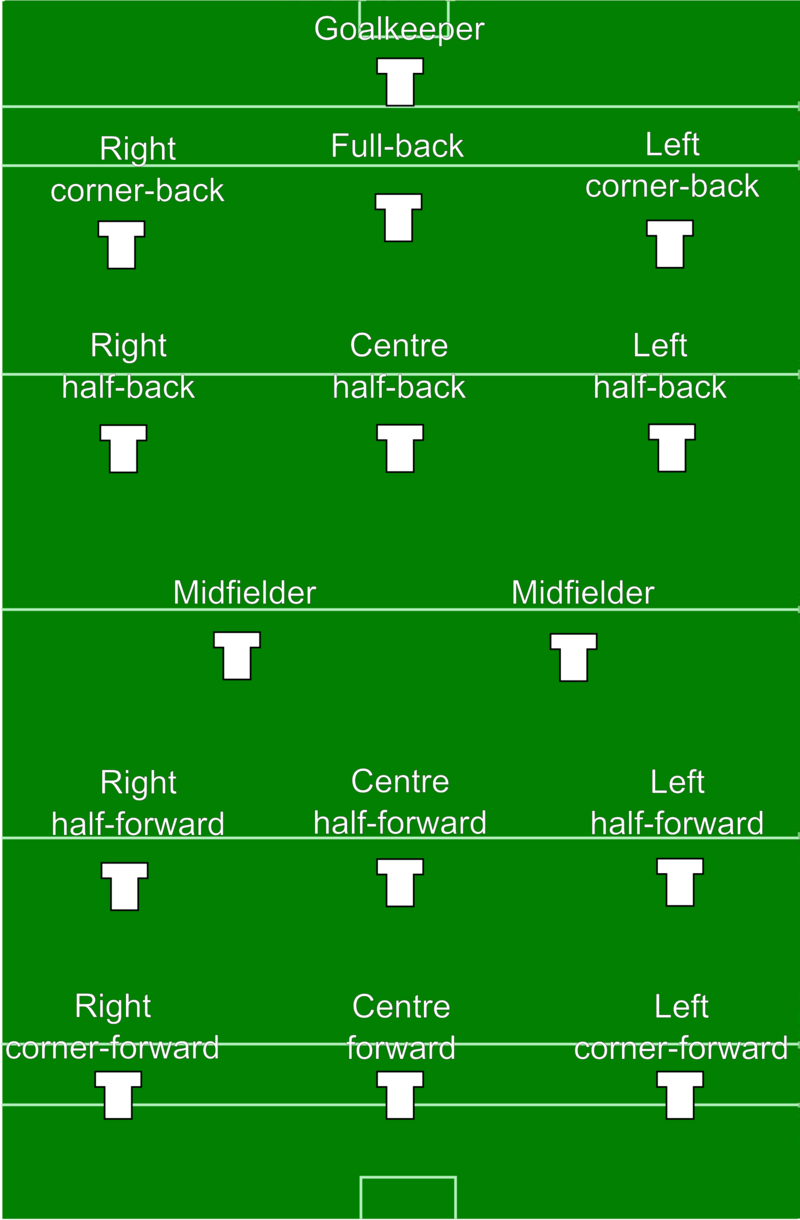

Teams consist of thirteen or fifteen players: a goalkeeper, three full backs, three half backs, two midfielders, three half forwards and three full forwards (see diagram). The panel is made up of 24–30 players and five substitutions are allowed per game. An exception can now be made in the case of a blood substitute being necessary. In the USA, there are only two players at the full back and full forward positions, for a total of thirteen players.

Helmets

From 1 January 2010, the wearing of helmets with faceguards became compulsory for hurlers at all levels. This saw senior players follow the regulations already introduced in 2009 at minor and under 21 grades. The GAA hopes to significantly reduce the number of injuries by introducing the compulsory wearing of helmets with full faceguards, both in training and matches. Hurlers of all ages, including those at nursery clubs when holding a hurley in their hand, must wear a helmet and faceguard at all times. Match officials will be obliged to stop play if any player at any level appears on the field of play without the necessary standard of equipment.

Timekeeping

Senior inter-county matches last 70 minutes (35 minutes per half). All other matches last 60 minutes (30 minutes per half). For teams Under-13 and lower, games may be shortened to 50 minutes. Timekeeping is at the discretion of the referee who adds on stoppage time at the end of each half.

If a knockout game finishes in a draw, a replay is staged. If a replay finishes in a draw, 20 minutes extra time is played (10 minutes per half). If the game is still tied, another replay is staged.

In club competitions, replays are increasingly not used due to the fixture backlogs caused. Instead, extra time is played after a draw, and if the game is still level after that it will go to a replay.

Technical fouls

The following are considered technical fouls (“fouling the ball”):

- Picking the ball directly off the ground (instead it must be flicked up with the hurley)

- Throwing the ball (instead it must be “hand-passed”: slapped with the open hand)

- Going more than four steps with the ball in the hand (it may be carried indefinitely on the hurley though)

- Catching the ball three times in a row without it touching the ground (touching the hurley does not count)

- Putting the ball from one hand to the other

- Hand-passing a goal

- “Chopping” slashing downwards on another player’s hurl

Scoring

Scoring is achieved by sending the sliotar (ball) between the opposition’s goal posts. The posts, which are at each end of the field, are “H” posts as in rugby football but with a net under the crossbar as in football. The posts are 6.4 m apart and the crossbar is 2.44 m above the ground.

If the ball goes over the crossbar, a point is scored and a white flag is raised by an umpire. If the ball goes below the crossbar, a goal, worth three points, is scored, and a green flag is raised by an umpire. A goal must be scored by either a striking motion or by directly soloing the ball into the net. The goal is guarded by a goalkeeper. Scores are recorded in the format {goal total} – {point total}. For example, the 1997 All-Ireland final finished: Clare 0–20 Tipperary 2–13. Thus Clare won by “twenty points to nineteen” (20 to 19). 2–0 would be referred to as “two goals”, never “two zero”. 0–0 is said “no score”.

Tackling

Players may be tackled but not struck by a one handed slash of the stick; exceptions are two handed jabs and strikes. Jersey-pulling, wrestling, pushing and tripping are all forbidden. There are several forms of acceptable tackling, the most popular being:

- the “block”, where one player attempts to smother an opposing player’s strike by trapping the ball between his hurley and the opponent’s swinging hurl;

- the “hook”, where a player approaches another player from a rear angle and attempts to catch the opponent’s hurley with his own at the top of the swing; and

- the “side pull”, where two players running together for the sliotar will collide at the shoulders and swing together to win the tackle and “pull” (name given to swing the hurley) with extreme force.

Restarting play

The match begins with the referee throwing the sliotar in between the four midfielders on the halfway line.

After an attacker has scored or put the ball wide of the goals, the goalkeeper may take a “puckout” from the hand at the edge of the small square. All players must be beyond the 20 m line.

After a defender has put the ball wide of the goals, an attacker may take a “65” from the 65 m line level with where the ball went wide. It must be taken by lifting and striking. However, the ball must not be taken into the hand but struck whilst the ball is lifted.

After a player has put the ball over the sideline, the other team may take a ‘sideline cut’ at the point where the ball left the pitch. It must be taken from the ground.

After a player has committed a foul, the other team may take a ‘free’ at the point where the foul was committed. It must be taken by lifting and striking in the same style as the “65”.

After a defender has committed a foul inside the Square (large rectangle), the other team may take a “penalty” from the ground from behind the 20 m line. Only the goalkeeper may guard the goals. It must be taken by lifting and striking and the sliotar must be stuck on or behind the 20m line (The penalty rule was amended in 2015 due to safety concerns. Before this the ball merely had to start at the 20m line but could be struck beyond it. To balance this advantage the two additional defenders previously allowed on the line have been removed).

If many players are struggling for the ball and no side is able to capitalize or gain control of the sliotar the referee may choose to throw the ball in between two opposing players. This is also known as a “Clash”.

Officials

A hurling match is watched over by eight officials:

- The referee

- Two linesmen

- Sideline official/standby linesman (inter-county games only)

- Four umpires (two at each end)

Players are cautioned with a yellow card, and dismissed from the game with a red card.

The referee is responsible for starting and stopping play, recording the score, awarding frees, noting infractions, and issuing yellow (caution) and red (order off) penalty cards to players after offences. A second yellow card at the same game leads to a red card, and therefore to a dismissal.

Linesmen are responsible for indicating the direction of line balls to the referee and also for conferring with the referee. The fourth official is responsible for overseeing substitutions, and also indicating the amount of stoppage time (signalled to him by the referee) and the players substituted using an electronic board. The umpires are responsible for judging the scoring. They indicate to the referee whether a shot was: wide (spread both arms), a 65 m puck (raise one arm), a point (wave white flag), or a goal (wave green flag).

Contrary to popular belief within the association, all officials are not obliged to indicate “any misdemeanours” to the referee, but are in fact only permitted to inform the referee of violent conduct they have witnessed which has occurred without the referee’s knowledge. A linesman/umpire is not permitted to inform the referee of technical fouls such as a “Third time in the hand”, where a player catches the ball for a third time in succession after soloing or an illegal pick up of the ball. Such decisions can only be made at the discretion of the referee.